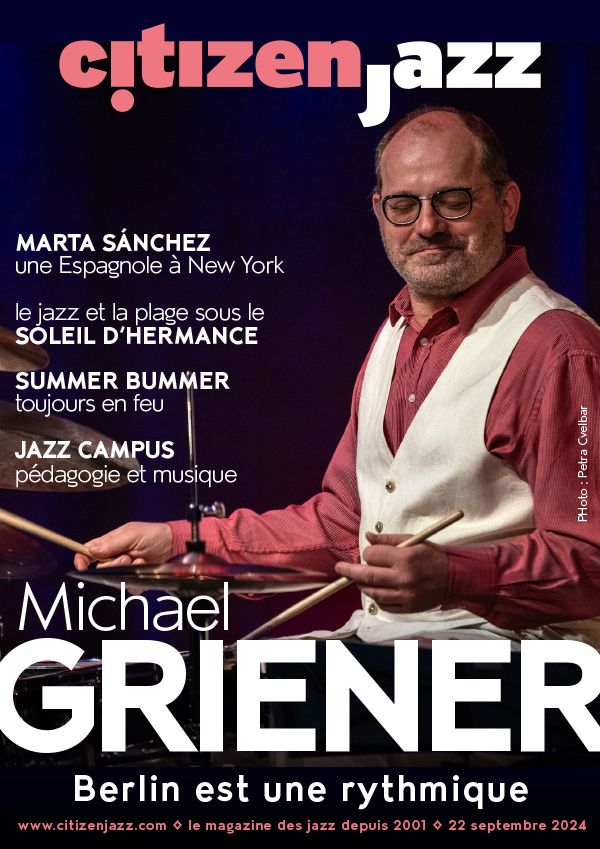

I feel more than honored; after 40 years in this music, this is the first time I made it on the cover of a magazine, and with such a lovely photo by Petra Cvelbar.

Many thanks to Franpi Sunship Barriaux for making this possible.

On top of that there are reviews of my three recent releases in the magazine: Griener Roder : Be Our Guest, Lina Allemano’s Ohrenschmaus: Flip Side and The Straight Horn of Rudi Mahall.

https://www.citizenjazz.com/Michael-Griener-Berlin-est-une-rythmique.html

Here’s the full article, translated into English:

MICHAEL GRIENER, BERLIN IS A RHYTHM

A conversation with Michael Griener, one of Europe’s most remarkable drummers

When you’re a music enthusiast or observer — especially of jazz — you naturally gravitate toward names that keep popping up. Michael Griener is one of those names. As a drummer closely associated with bassist Jan Roder, he’s worked with the likes of Ulrich Gumpert, Alexander von Schlippenbach, and Silke Eberhard — a veritable map of German and European jazz. The deep musical bond between Griener and Roder, built over three decades, is showcased in the brilliant new album Be Our Guest, packed with previously unreleased material. More than just a compilation, it’s a sweeping portrait of their shared musical journey — a gem of humility and joyful expression, much like this first in-depth interview with a musician who represents the magic and vitality of Berlin.

– Michael, you and Jan Roder have been a rock-solid rhythm section for 30 years now. How did you first meet?

Jan and I met in the early ’90s in Hanover, where he was briefly studying jazz double bass. I had previously been a guest student at the same university while I was still in high school, but I never really felt like studying formally — I already had too much going on in my head. Jan came from a rock background but turned to jazz after hearing Cecil Taylor, which deeply impressed him. Unfortunately, his first jazz bass teacher convinced him he had to learn standards before he could play freely, so he took a bit of a detour.

At that time, I had already been playing professionally for a few years, having dropped out of school. I had experience in both straight-ahead and free jazz because I started playing both very early on, often with Rudi Mahall and others.

Eventually, Jan and I played in several groups — some more traditional, but increasingly doing our own thing. Our trio with saxophonist Christof Knoche, which is featured on our CD, was really the start of our rhythm section concept.

– How do you explain — if that’s even possible — the chemistry between the two of you? Do you have role models?

Of course, we each have our instrumental influences, but as a rhythm section, we never tried to imitate anyone. What really helped was playing together a lot, in very different settings, and developing our style organically. The Mingus/Richmond team is definitely a reference, but we don’t really have a leader — decisions are made more intuitively. We’ve known each other a long time, even shared an apartment in Berlin for a few years. We’re quite different — musically and personally — and we give each other plenty of space to be ourselves. Most importantly, we know how to make the most of each other’s strengths and weaknesses for the sake of the music.

– In Berlin, it seems like the Griener/Roder rhythm duo has become the go-to for musicians wanting to tap into the city’s scene. Is your anniversary album a reflection of that?

Honestly, I don’t feel like we’re perceived as any kind of special unit. At least, it feels like only the musicians we actually play with are paying attention to what we’re doing. We just gave our first joint interview after all these years and haven’t won any awards yet. But who knows what the future holds?

The goal of the CD was to bring together all the work we’ve done and showcase what we’ve been up to over the past three decades. We never really thought about it — we just kept playing. But during the lockdown, instead of playing, we started talking and realized it had almost been 30 years. That seemed like a good reason to celebrate.

– Be Our Guest feels like a big European jazz family reunion — almost like a giant Citizen Jazz poster. Is that something you’re proud of? Does the album tell a story?

Jan and I have spent most of our lives in Berlin. We came in the ’90s to play, not to chase a career or make money. The city was so cheap back then that money wasn’t really a concern. You could pour all your energy into the music. The scene was very open — no one had anything to lose or take away from anyone else. We played with anyone who wanted to play, and pretty much everyone wanted to. Otherwise, you wouldn’t have enjoyed living with a coal stove, no bathroom, and an outdoor toilet — which was our living standard when we moved to East Berlin.

Over the years, that led to connections that feel almost like family. Our “family” includes many well-known and lesser-known musicians who all share a deep musicality. There are lots of interconnections, some we didn’t even know about ourselves. I think we’re a little proud to have brought musicians together and to have been part of it for so long.

– The trio format seems to be a recurring theme in your work — your group with Ellery Eskelin, or of course Lacy Pool with Uwe Oberg. Is that your ideal setup? Have you considered solo work — or a duo record with Jan?

Yes, I think the trio is my favorite format. It allows for direct exchange, but with a bit more structure than a duo, even though I like that too.

HAVING A GUEST MUSICIAN REALLY TESTS OUR EMPATHY — AND MAKES US PLAY EVEN BETTER.

I’ve played a few duo shows with Jan, but when we add a third musician, it really pushes our listening and responsiveness. We know each other so well that playing without that “distraction” is almost too easy.

I am seriously considering a solo recording, though I approach it with a lot of respect. For me, music is about communication — about being in situations where things don’t go as expected and making the most of it. That’s what I enjoy the most. Playing solo removes that feedback loop and puts it all on me. There’s nowhere to hide. I plan to try it this year, and I hope I’ll like the result.

– One of your closest collaborators is Rudi Mahall. In your trio Ouàt, you invited him to record the spirited The Straight Horn of Rudi Mahall. Was that another nod to Lacy — or just a desire to play, in the most joyful sense?

Rudi was literally the first person I ever made music with — not long after I got my first drum set. Back then, he only played straight B♭ clarinet; the bass clarinet came later. We grew up together musically and personally, influencing each other along the way.

Of course, Steve Lacy is one of our heroes and means a lot to us. But the play on “The Straight Horn” was also the main idea of the record.

With Simon Sieger and Joel Grip in Oùat, we have deep respect for tradition, but also a strong drive to immerse ourselves in the music. So they were perfect for the project. I brought all three into Joel’s studio and made the recordings myself. But it was also a kind of thank-you to Rudi.

I come from a pretty modest background. If I hadn’t met Rudi, I probably wouldn’t have become a musician — I didn’t even know it was an option. He was determined to be a pro musician even when he could barely play. Meeting him made me realize it was possible. In that sense, I owe him the happiness of my life.

– One of the groups on Be Our Guest is the fantastic Die Enttäuschung, a band historically linked with Alexander von Schlippenbach. Can you tell us more? What role does the pianist play in your music — or in your connection with Roder?

After Rudi and I moved to Berlin in 1994, we didn’t play together for a while. That’s when Die Enttäuschung was formed. Monk was always important to us, and we tried playing his tunes from the start. Sheet music was hard to find, and Brian Priestley’s transcription book was vital back then.

From what I know, Die Enttäuschung started as a Monk rehearsal project, kind of like Steve Lacy and Roswell Rudd’s School Days. Jan later replaced the original bassist, and they started writing their own music. Alexander von Schlippenbach joined later — by then, most of the Monk material had already been arranged.

The original drummer, Uli Jeneßen, left in 2012, and after trying a few others, they ended up with me in 2016. Around that time, Rudi and I played together again in Squakk (with Christof Thewes and Jan), and the two groups merged for a while, making Die Enttäuschung a quintet.

In 2017, for Monk’s centenary, Monk’s Casino had a few concerts planned. Since I knew Monk’s entire catalog and could arrange easily, I joined that group too.

Schlippenbach and Aki Takase live in my neighborhood, and over the years, I’ve played with them in many projects, often with Jan.

I SEE SO MANY YOUNG MUSICIANS MOVING TO THE CITY WHO HAVE TO EARN SO MUCH JUST TO LIVE THAT THEY HARDLY HAVE TIME TO MAKE MUSIC.

In November 2021, Jan and I performed at Au Topsi Pohl in Berlin as part of a weeklong residency. We played with eight different groups, which make up most of the second CD on Be Our Guest. There’s a double LP of Monk’s Casino’s concert, and one track is also included on Jan’s and my CD.

– Monk and Lacy appear frequently in your recordings. Is there another jazz musician you’d like to honor through your music?

Monk and Lacy are very important to me, as are Mingus, Ellington, and Ornette. It all started for me with Benny Goodman and Gene Krupa. Honestly, any musician who’s inspired me is important.

But I think it’s crucial not to just play other people’s music — no matter how much you love it.

As Lester Young said, “You can’t join the throng until you sing your own song.”

You must have something to say. You have to make a contribution.

– In your recent trios, we’ve heard you with Céline Voccia and Taiko Saito. What’s your take on the musicians — especially the international ones — who’ve moved to Berlin? Has it really become a paradise for improvised music?

There are so many great musicians in Berlin, and more keep arriving, even though things aren’t as easy as they were in the ’90s. I see lots of young players who have to work so much just to survive that they barely have time to make music.

For me, though, it’s a wonderful situation — I’m constantly meeting new musicians. Some move here, others stay for a while, but there’s always fresh inspiration and new connections. If you need ideas or contacts, you can find ten concerts a night to help with that.

Unfortunately, the city lacks infrastructure — no public radio to document the music, and not much press coverage. It’s gotten a bit better, but considering the sheer volume of music here, it’s still underrecognized.

There are lots of opportunities to play, but you have to be mindful about getting noticed, especially if you’re new in town. But if you seize the chances and stay focused, life here can still be very rewarding.

– What are your upcoming projects?

My trio Ouàt with Simon Sieger and Joel Grip is picking up steam — we’re on tour this year in Belgrade, Budapest, and Berlin. We’ve got new recordings planned for next year.

I’ve also started a new trio with Serbian pianist Marina Džukljev and Swiss bassist Christian Weber, and another with Rudi Mahall and Swiss guitarist Florian Stoffner.

And I’ve finally decided to record some solo material — even though it’s a challenge.

On top of that, I’ve already met so many new musicians this year that I have no idea what next year will look like. I’m curious myself.

— Interview by Franpi Barriaux // Published September 22, 2024